Miss Rumphius was not perfect. Neither was Barbara Cooney.

This fact doesn’t keep me from celebrating Miss Rumphius in the first entry in a blog where I call out and study examples of awesomeness.

On the contrary, their imperfections are productive–allowing me to tease out, first, what I mean by awesome and, second, to actually feel inspired, in spite of my own imperfections, by two people who accomplished so very much in their lifetimes.

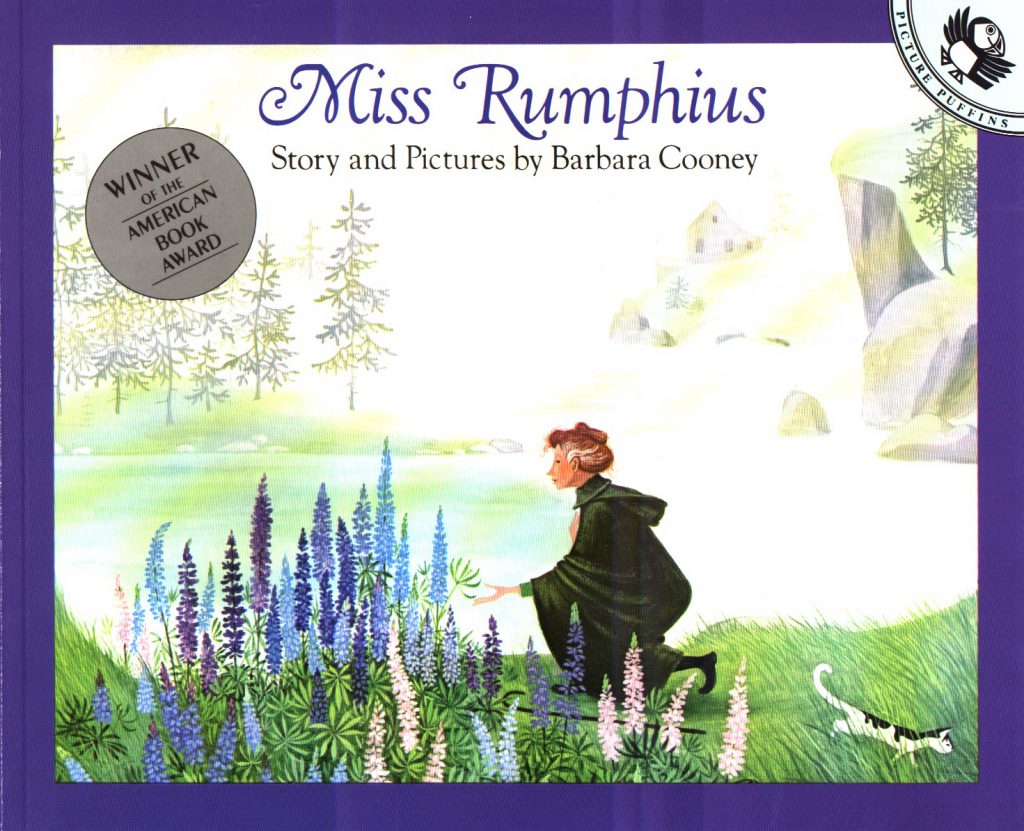

Miss Rumphius is Barbara Cooney’s story–in words and paintings– about the narrator’s inspiring great-aunt, Alice Rumphius.

Alice’s own inspiration was her grandfather–an artist and an immigrant. She wanted to be just like him–to visit faraway places when she grew up and to live by the sea when she grew old. That was fine with him, but he pushed her to add one more thing to her to do list: “You must do something to make the world more beautiful.”

There are so many things about this book that I consider awesome. It starts when Alice Rumphius is little and old. Humanizing, and thus reminding us to value, little old women. Alice’s grandfather provides an older male model of creativity who encourages Alice’s expression of her own interests and drive. Yes, he tells her, you can do those things and more. You matter, not just to your own happiness, but to the world. You have a duty to make the world a better place. You have a mission. How magical that little Alice is validated in her dreams and invested with a mantle of duty, mission, and importance AND that the author manages to tell the rest of child Alice’s story in just three lines. “In the meantime Alice got up and washed her face and ate porridge for breakfast. She went to school and came home and did her homework. And pretty soon she was grown up.”

There are a couple reasons this works. First of all, that narratorial voice that relates Alice’s actions only comes in once we’ve already gotten both Alice’s response to her grandfather in direct discourse (“‘All right,'” she says) and a peek inside Alice’s head: “But she did not know what that could be”.

The gap that exists here between Alice’s words and her thoughts is, of course, the space in which the rest of the story unfolds.

I had never heard of this book (perhaps because I was already 8 and reading chapter books on my own when it came out in 1982) until I got it in the mail this fall. My mother-in-law sent both of my children a book as a back-to-school gift (an awesome tradition I’m not sure we actually have since this is the first time it happened). I must say it didn’t look particularly promising with its frumpy title and its proper-looking lady on the cover. I apparently don’t imagine old-timey ladies with flowers bearing liberating messages for my daughter.

I had never heard of this book (perhaps because I was already 8 and reading chapter books on my own when it came out in 1982) until I got it in the mail this fall. My mother-in-law sent both of my children a book as a back-to-school gift (an awesome tradition I’m not sure we actually have since this is the first time it happened). I must say it didn’t look particularly promising with its frumpy title and its proper-looking lady on the cover. I apparently don’t imagine old-timey ladies with flowers bearing liberating messages for my daughter.

Anyway, my mother-in-law sent it, and my little girl demanded I read it to her, so I did.

There really is nothing like reading a book to your child when you are both truly present to each other, looking into each other’s eyes, as you hear together, for the first time, the words, and the letters and sounds and hidden messages of those words bloom into meaning in your minds, and you discover, as the message is deciphered, that it is the very expression of one of your dearest wishes for her. And she beams back at you as if to say, “Thank you for thinking I matter! and that I can–and will–make something as big as the world a better place!”

Upon further reflection (because when tears present you must reflect) you understand that the tears are there, not only because Barbara Cooney paints before you a dream you have for your child (one you haven’t yet found the words to tell her, but there it is, on the page and in your voice and you’ve told her and you are moved), but also because the dream Barbara Cooney describes is also your dream for yourself.

Especially in this moment when you are thinking about leaving your oh-so-secure job, because you are audacious enough to believe you can do something to make the world a more beautiful place, but you still do not know what that could be. But there it is again, this time in black and white, the dream that you matter, that the world just might be a more beautiful place for you having been in it.

Where were we? Oh yes. The gap that exists between Alice’s words and her thoughts–the space in which the rest of the story unfolds.

I am in that place. Awake to the fact that I matter, that I have a gift to give the world but clueless as to what it is. What does Alice do when she is in that gap? “She got up and washed her face and ate porridge for breakfast. She went to school and came home and did her homework.”

Hmm.

I am interpreting this to mean that sometimes you have to do the work even though you don’t know why or where you are headed exactly. What’s the work? For right now, I’m going to write this blog even though I’m not sure what that does for me or where it takes me. Something tells me that I want to amplify what is awesome.

All this and we are only on page three of Miss Rumphius. Worry not. As you’ve seen, Barbara Cooney can do mighty things in three lines.

Miss Rumphius grows up. She works in a library. She has wonderful adventures, a right inspiration to solo women travelers. Miss Rumphius grows old and lives in a lovely house on the water. She is almost perfectly happy, but something is missing. And guess what? It isn’t a husband. It isn’t children.*

It’s that she has one more thing that she has to do.

I have to do something to make the world more beautiful.

But Miss Rumphius fell ill. She was old. What could she do?

Inspiration struck and she sent off for five bushels (!) of lupine seed. Soon, the lupines painted the school yard, the church yard, and the country lanes all around. She became known as “The Lupine Lady”.

As the New England Historical Society points out, “There was a real Miss Rumphius who lived in Christmas Cove and secretly planted lupine seeds to adorn Maine’s roadsides and meadows.” Her name was Hilda Hamlin, née Edwards. After Yankee magazine told her story in 1971, they published an editor’s note: “Mrs. Hamlin was overwhelmed with hundreds of letters and almost as many visitors following publication of the original article in the June, 1971, Yankee; most of the correspondents and callers begged for sample seeds. Out of deference for Mrs. Hamlin’s advanced years, the editor feels called upon to remind would-be roadside gardeners that “Hilda Lupina” is not in competition with Burpee and other seed suppliers, and, happy as Hilda is with her fan mail, she is no longer up to distributing souvenir seeds of receiving and entertaining hordes of callers at Jupiter Knoll.”

Conflating fact and fiction as our minds do, we see that Miss Rumphius really did make the world more beautiful in a big way–she found something meaningful to her that she could make happen in spite of her age and infirmity–and her act was noticed and appreciated. Completing the imitation of her beloved grandfather, Miss Rumphius entrusts a mission to her great-niece and namesake, Alice, the narrator: she too must do something to make the world more beautiful. Like her great-aunt, little Alice leaves the question in suspense, as she doesn’t quite know what that might be. The reader, who understands on some level that little Alice figures the author, has a good idea that the thing little Alice grew up to make, her contribution to a world more beautiful, is in fact the illustrated book of inspiration they hold in their hands and read to their own little child.

***

Now, it turns out that lupine is an invasive species. Stephen Heard discusses this problem in his thoughtful blog post: To love or to hate Miss Rumphius? Lupinus polyphyllus is at home in the northwestern U.S. and Canada. Not in Maine.

Furthermore, the American Indians in Children’s Literature blog also points out, and invites discussion around, the fact that Barbara Cooney depicts cigar store Indians without any critical distance.

So no, not perfect.

These are real problems with the book, not negligeable or niggley points. Both errors go beyond simply getting a fact wrong. Both errors are born of, and proliferate, ignorance. Both errors are destructive. Like encouraging the spread of an invasive species, perpetuating a stereotypical and unexamined representation of a group of people is not only a mistake in the present, but it has continuing consequences. Native species can’t grow where invasive species are taking up space and resources–and if they aren’t growing, they aren’t reproducing, and the imbalance worsens.

***

Awesome is not perfect. Awesome is trying to make the world better–not only for ourselves, but for others too.

We all face obstacles in our lifetimes. We all have gifts.

Barbara Cooney was born in 1917 and graduated from college in 1938–at a time when a tiny percentage of Americans managed to do so (5.5% of men and 3.8% of women graduated from college in 1940, the first census to keep track of this statistic). The fact that Barbara Cooney accomplished this points up not only her innate gifts and work ethic, but also her privileges.

As her NYT obituary indicates, Barbara Cooney won the Caldecott Medal for illustration twice and each prize spurred her to take new risks. After the first, in 1958, she began to paint, and after the second, in 1980, she began to write her own stories to illustrate (including Miss Rumphius). She was talented and brave, but like all of us, did even better with encouragement.

We all have limitations. Not only are we limited by our context, but we are limited by our very nature as humans. We can’t know the future. We can’t imagine all of the possible consequences of our actions. In spite of this, we have to act. We have to stand up and tell our stories as best we can. We have to encourage the next generation to believe in a more beautiful world and their role in shepherding it into existence.

You know what is awesome? People who contribute to a culture of truth, a culture of discussion, a culture of trying.

It is a risk to write stories for children (one Cooney took 110 times). It is not a risk to enjoy warm underwear straight from the dryer. Both are awesome, indeed, but the former is what I will focus on here. Where there is risk, there may be error, but taking a risk to make the world better — that is something worth celebrating.

*I must mention another inspiring text where the main character is a woman and manages to grow old while grounding her happiness in something other than husband and children: Letters of a Peruvian Woman (Lettres d’une peruvienne). And yes, Françoise de Graffigny, was heavily criticized for her character’s choices. Nevertheless, her novel was one of the bestsellers of the eighteenth century. Speaking of Peruvians, did you know that you can eat lupine seeds? Called tarwi or chocho, it comes from the Andean Lupin (Lupinus Mutabilis). This dense, white bean is rich in protein (even more than quinoa and soy beans), contains healthy fats (omega-3s) and is high in fiber and minerals.